Dharavi is Asia’s largest slum. Covering roughly 2.4 square kilometers of what has become prime Mumbai real estate, it is home to an estimated 1 million people and one of the most densely populated places on earth. Made famous as the location of the Oscar winning Slumdog Millionaire, it’s also featured in a number of other movies portraying dreams of escaping a life of grinding poverty, and as a hotbed of organised crime. Many of Dharavi’s residents find these portrayals insulting and offer a counter narrative of an industrious melting pot whose residents pride themselves on being hard working and ‘atmanirbhar’, meaning self-reliant.

Whilst there are a few suprisingly substantial buildings in Dharavi, the infrastructure and sanitation are very poor. A chaos of improvised power lines hang over the area like a giant, haphazard spider’s web. Water is only supplied between 4 and 9 pm.

Dharavi’s original inhabitants were a Koli fishing community. In the 1860s Tamil Muslim traders also began to settle in the area.

Low caste Dalits from Tamil Nadu soon followed in the wake of the Muslim traders, establishing the tanneries and leather workshops that were to become one of Dharavi’s core industries. Over time they were joined by migrants from all over India and today Dharavi is a multi-faith community where over a dozen languages are spoken.

A leather worker takes a short breather from the noxious fumes of the tannery.

Pottery is another of Dharavi’s core industries. Dharavi’s potters mostly live and work in the laneways of the Kumbharwada – meaning ‘potter colony’. The area is one of Dharavi’s oldest neighbourhoods, established by Gujarati artisans forced to relocate from their original settlement in the south of the city during the second half of the 19th Century.

Kumbharwada is largely made up of tool-houses – hybrid buildings with a workshop on the ground floor and residence above. Living cheek-by-jowl with their relatives and fellow potters, the area has a particularly strong sense of community.

The pots, bowls, vases, saucers, lanterns and lamps made in Kumbharwada are sold in the local market, across India and as far a field as Japan and Germany.

The brick kilns that crowd the laneways are often fuelled with scraps of fabric from Dharavi’s textile industry – here nothing goes to waste. Living where you work may be convenient but it can also have drawbacks. The acrid smoke produced by the kilns does nothing to improve Mumbai’s already poor air quality, coating Kumbharwada’s buildings with toxic soot.

Many of Dharavi’s cramped workshops struggle with aging machinery, poor ventilation and little if any natural light. Despite these hardships, according to the The Times of India, it is estimated that Dharavi’s economy is worth approximately 1 billion US dollars per annum and employs some 250,000 workers.

Textiles are another of Dharavi’s main industries. Catering mostly to the domestic market, workers put in shifts of up to 14 hours, usually getting paid on a piece-rate basis and earning around Rs 150 per day.

Many small businesses are run out in the alleys with nothing more than a power supply and makeshift furniture.

With space at a premium, every available nook and cranny is put to work.

Around 60% of the city’s plastic is recycled in Dharavi, as are computer parts, car batteries, cardboard boxes and anything else that can be salvaged from the estimated 9,400 tonnes of waste generated by the city every day.

A primary school teacher awaits her students. Education is highly valued and there are around 60 primary and 13 free secondary schools, as well as a small number of private schools.

The literacy rate in Dharavi is high for a slum area, hovering somewhere around the 70% mark.

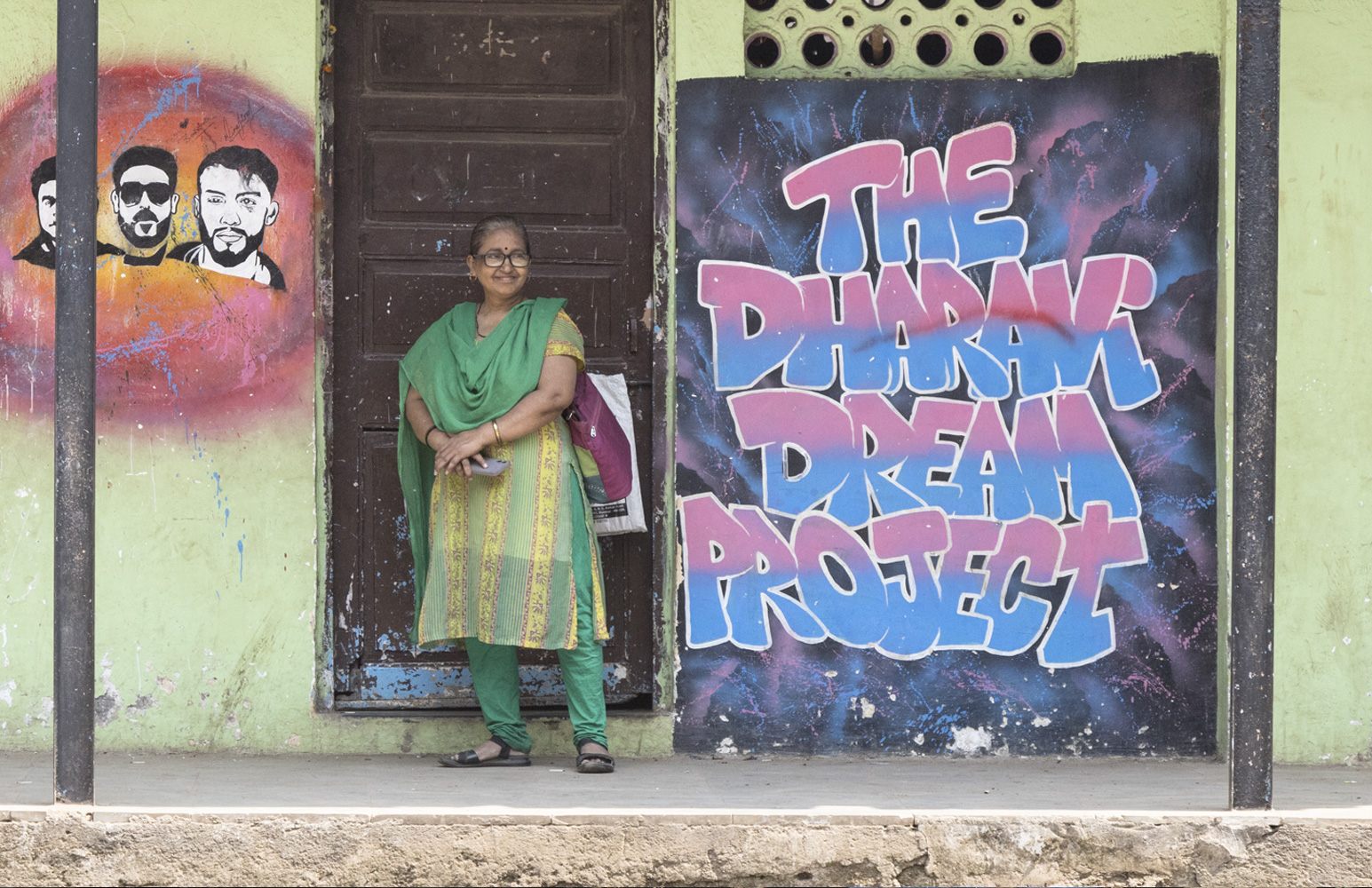

Dharavi’s notoriety has spurred a growing tourist trade, the proceeds from which directly help to boost the local economy. An estimated 15,000 visitors per year are guided through its labyrinthian laneways by entrepreneurial locals. Whilst the undeniable deprivation is plain for all to see, it is the strong sense of community and astonishing productivity that is likely to make the greatest impression. However, the future of Dharavi looks precarious, with Gautam Adani – the billionaire industrialist and close friend of Narendra Modi – recently having been awarded a contract to redevelop the area.